The frequency of flooding in coastal communities is increasing, even when there is not a storm. These floods go by many names — sunny day floods, high tide floods, nuisance floods — and they can be caused by sea level rise, tides, wind, groundwater, rainfall runoff and river flows. In projects supported by North Carolina Sea Grant and the National Science Foundation, Dr. Katherine Anarde and Ph.D. student Thomas Thelen are trying to measure, model and understand the impacts of chronic shallow flooding in coastal North Carolina.

Tides now rise and fall on higher average sea levels, resulting in a higher frequency of “sunny day” flooding of roadways during high tides. Sea water can also infiltrate drainage networks at low tide levels such that ordinary rain storms now cause flash floods. The travel disruptions from flood-induced street closures, as well as damage to vehicles and infrastructure from salt water, can impose chronic stress on communities. At a local level, the causes and frequency of these floods are often not well understood, nor are the impacts to people and communities — partly because flooding by large storm events like hurricanes receives more attention, and partly because these hyper-local, multidriver floods are difficult to monitor and predict.

As part of a two-year North Carolina Sea Grant project that began in February 2022, Anarde and Thelen, alongside other researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, are working with the Town of Carolina Beach to deploy a real-time water level sensor network to continuously measure the stormwater network capacity. This data will validate a coupled hydrodynamic and hydrologic model of flooding in the town, which will then be used to simulate future flood risk and potential adaptation strategies.

“I am passionate about this project because it is science for action, shaped by community needs,” Thelen said. “The findings from this research will directly inform coastal resilience solutions and policies that will help our waterfront communities adapt to the rising seas of the coming decades.”

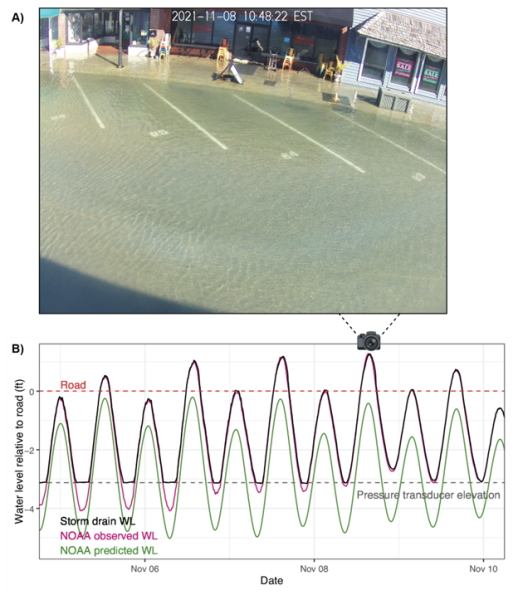

During the spring 2022 semester, Thelen organized a 20-person build-a-thon where students from NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill learned and utilized basic electrical engineering skills to construct 10 Sunny Day Flood Sensors (SuDS). These sensors have been deployed across North Carolina, including in Beaufort and New Bern, as part of the larger Sunny Day Flooding Project led by Anarde and Dr. Miyuki Hino, assistant professor at UNC-Chapel Hill. Real- time water level data from the SuDS are displayed online at go.unc.edu/sunny. Water-level data from the drain is supplemented with real-time photographs capturing the spatial extent of flooding. Email alerts are triggered when water levels approach the roadway, which allows for proactive implementation of flood warning measures by town staff. The SuDS in Beaufort has been operational for one year and has recorded 35 roadway flood events.

The Sunny Day Flooding Project was highlighted in the PBS documentary State of Change earlier this year.